BESA-By Dr. George N. Tzogopoulos: Light at the End of the Tunnel for Greece?

BESA Center Perspectives Paper No. 950, September 16, 2018

BESA Center Perspectives Paper No. 950, September 16, 2018EXECUTIVE SUMMARY: Maladministration, overspending, cronyism, and statism over a period of decades made Greece the weakest link in the Eurozone when the world financial crisis hit Europe in 2009. To avoid a chaotic default and an exit from the European system, Greece had no alternative but to accept bailouts offered by the EU and the IMF in exchange for austerity measures and structural reforms. The third and final one expired on August 20, 2018. The day after finds Greece with relatively stable public finances but unable to immediately regain market confidence. Above all, the tendency of politicians to put their political interest above the national one remains even as the society is suffocating from social problems and is pessimistic about the future.

Nine years ago, during a pre-election period in Greece in September 2009, two powerful political parties – then-incumbent conservative New Democracy and center-left PASOK – presented their agendas to citizens. The former told the truth about the country’s economic status and the need to take measures (though it only decided to do so after years of government inertia and being behind in all opinion polls). The latter preferred to ignore reality and promised the Greeks a lot of money. They won the election.

The euphoria did not last long. PASOK was not able to refinance the country’s debt by accessing international markets. By contrast, it had to immediately reduce the budget and current account deficits, as well as ask for a financial lifeline from the EU and the IMF in May 2010. It was thus in desperate need of political consensus despite its stance while in opposition. New Democracy – now the main opposition – did not back difficult measures in Parliament, hoping to benefit from the damage to PASOK and return to power. This tactic was successful: the party won the national election of June 2012.

The cynical disagreements between New Democracy and PASOK according to their ephemeral political needs highlight flaws in Greek politics that persist even in critical periods.

The responsibility of the two main parties is twofold. First, they undermined the future of young Greeks for decades by creating a huge, unsustainable debt, preserving a bubble, tolerating corruption, and relying on clientism, nepotism, and statism. And second, they failed to cooperate and accelerate an exit from the crisis when it erupted. As a result, while other problematic states of the Eurozone – Cyprus, Ireland, and Portugal – managed to return to normalcy after receiving initial financial assistance from the EU and the IMF, Greece was in need of a second bailout in February 2012 and a third in August 2015.

Greek citizens also bear some responsibility. They tend to prefer easy solutions and approve of political favoritism, and they are allergic to the truth. In 2014, two years after the second bailout package, the national economy was recovering. Greece – under a coalition government of New Democracy and PASOK, which had forgotten their past rivalry and became political allies – created a budget surplus for the first time. However, the populist leftist party, Syriza, had begun in June 2012 to emerge as the new pole in Greek politics. Once again, there was no consensus in the name of a greater national good. The name of the parties had changed, but the problem remained unsolved.

Syriza cultivated illusions in Greek society instead of assisting the “Grecovery” and contributing to the completion of the second bailout. It promised to cancel the debt, renegotiate the bailout, and find funds in countries like Russia and Venezuela. It presented itself as a fresh political force with the potential to bring about change.

In December 2014 Syriza provoked an early election, and in January 2015 it defeated New Democracy. It took Syriza and its minor coalition partner, the Independent Greeks, all of six months to hit reality and vote for a third bailout in August 2015. As the Grexit risk was looming and several of Syriza’s MPs preferred a return to the drachma, New Democracy voted to keep the country in the common currency. One month later, Syriza – now more mature politically and without anti-EU MPs – won a snap election and re-formed a government with the Independent Greeks.

The Syriza-Independent Greeks government acted against their ideology and refuted critics by completing all of the four required reviews of the third bailout by June 2018. It did so without counting on political support from New Democracy. The conservative party preferred to employ the usual tactics of all main opposition parties to safeguard its own return to power in the next national election.

In a highly polarized political atmosphere, the Greek government recently announced the exit from the bailout. Generally speaking, the progress achieved since 2010 has been impressive. In spite of the dramatic setback of the first six months of 2015, Greece is now maintaining a budget surplus and has managed to decrease its current account deficit. Some important privatizations have taken place. Significant reforms are making the Greek pension system sustainable, tackling tax evasion, introducing transparency into public contracts, and boosting e-governance.

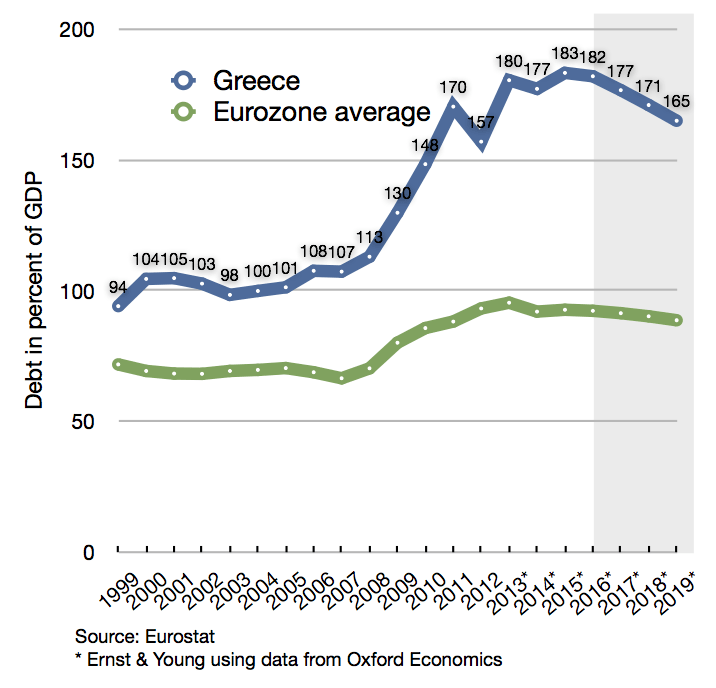

Moreover, the issue of the Greek debt has been settled. In 2012, the private debt of Greece was restructured and private bondholders were forced to accept losses exceeding 50%. As far as the public debt is concerned, a June 2018 Eurozone decision announced practical steps to improve its profile. If additional measures are required, they will be discussed at the Eurozone level in 2032, when Greece’s grace period will end.

Some skeptics argue that the Eurozone did not safeguard the sustainability of the Greek public debt. From an economic perspective, they are right. However, the Eurozone ministers could not ignore the political aspect. The Lisbon Treaty does not allow a normal debt haircut. Further to this, national parliaments and public opinion in Eurozone member states might not easily accept a settlement forgiving a significant part of Greece’s public debt as it has been accrued since 2010.

What matters more is that the Eurozone not abandon Greece but stand by its side. Against this backdrop, the country is leaving the bailout with a sizeable cash buffer of €24.1 billion to facilitate its smooth return to the markets in the next two years. Of course, the exit from the bailout does not signal an end to the adventure. Although Greece is not expected to receive additional loans from the EU and the IMF, it has to continuously implement reforms and sustain bailout objectives in order to pay back all its creditors over the medium and long term. The Greek government has already committed to maintain a primary surplus of 3.5% of GDP until 2022 and possibly 2.2% of GDP from 2023 until 2060.

The main problem is that Greek governments – irrespective of their political orientation – rely heavily on cuts and taxes to achieve surpluses. They do not always support healthy public or private investment but prefer to spend funds to serve political goals. Under these circumstances, unemployment is on the rise. The public sector has largely frozen hiring and when it recruits, non-transparent criteria are frequently applied. For its part, the private sector is suffocating due to high taxation and limited access to cheap credit. As a consequence, young people are looking for jobs abroad, depriving Greece of hope and dynamism and worsening the problem of an aging population.

For years, if not decades, to come, Greece will be under “enhanced surveillance” by the European Commission to remain on track. The stabilization of public finances has not yet been accompanied by a sustainable growth rate to help the economy breathe. Perspectives are not bright either. Greek politicians are unable to build on consensus and jointly support a growth plan by undertaking a national ownership of reforms. The ongoing political debate between Syriza, which is replacing PASOK in domestic politics, and New Democracy is being conducted almost exclusively around pension cuts, which have already been voted for. For political reasons, Syriza opposes a post-bailout credit line guaranteeing lower interest rates and seeks to spend funds from the budget surplus to boost its social profile in view of the forthcoming election. For its part, New Democracy is promising better days without Syriza in power but provides no details on how it will meet agreed fiscal targets.

The inability of Greek politicians to inspire the society and leave a legacy of unity and vision remains a central problem more than eight years after the first bailout. Even when the economy is improving, politics does not allow for real optimism. The Greek crisis is primarily political, not economic.

Dr George N. Tzogopoulos is a BESA Research Associate, Lecturer at the Democritus University of Thrace, and Visiting Lecturer at the European Institute of Nice.

Dr. George N. Tzogopoulos (Ph.D. Loughborough University) specializes in media and international relations as well as Chinese affairs.