BESA, By Emil Avdaliani: The China-US Confrontation: A Russian View

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY: China and the US have different geopolitical imperatives, so tensions are bound to increase between the two powers. Russia’s position in the nascent confrontation will be important to watch, as it is simultaneously under pressure from the West and in the shadow of Chinese economic strength. Russia will likely see US-China competition as providing an opportunity to improve its own geopolitical position.

China, which is poised to become a powerful player in international politics thanks to its economic rise and concurrent military development, has strategic imperatives that clash with those of the US. Beijing needs to secure its procurement of oil and gas resources, which are currently most available through the Malakka Strait. In an age of US naval dominance, the Chinese imperative is to redirect its economy’s dependence – as well as its supply routes – elsewhere.

That is the central motivation behind the almost trillion dollar Belt and Road Initiative, which is intended to reconnect the Asia-Pacific with Europe through Russia, the Middle East, and Central Asia. At the same time, Beijing has a growing ambition to thwart US naval dominance off Chinese shores. With these factors involved, mutual suspicion between Beijing and Washington is bound to increase over the next years and decades.

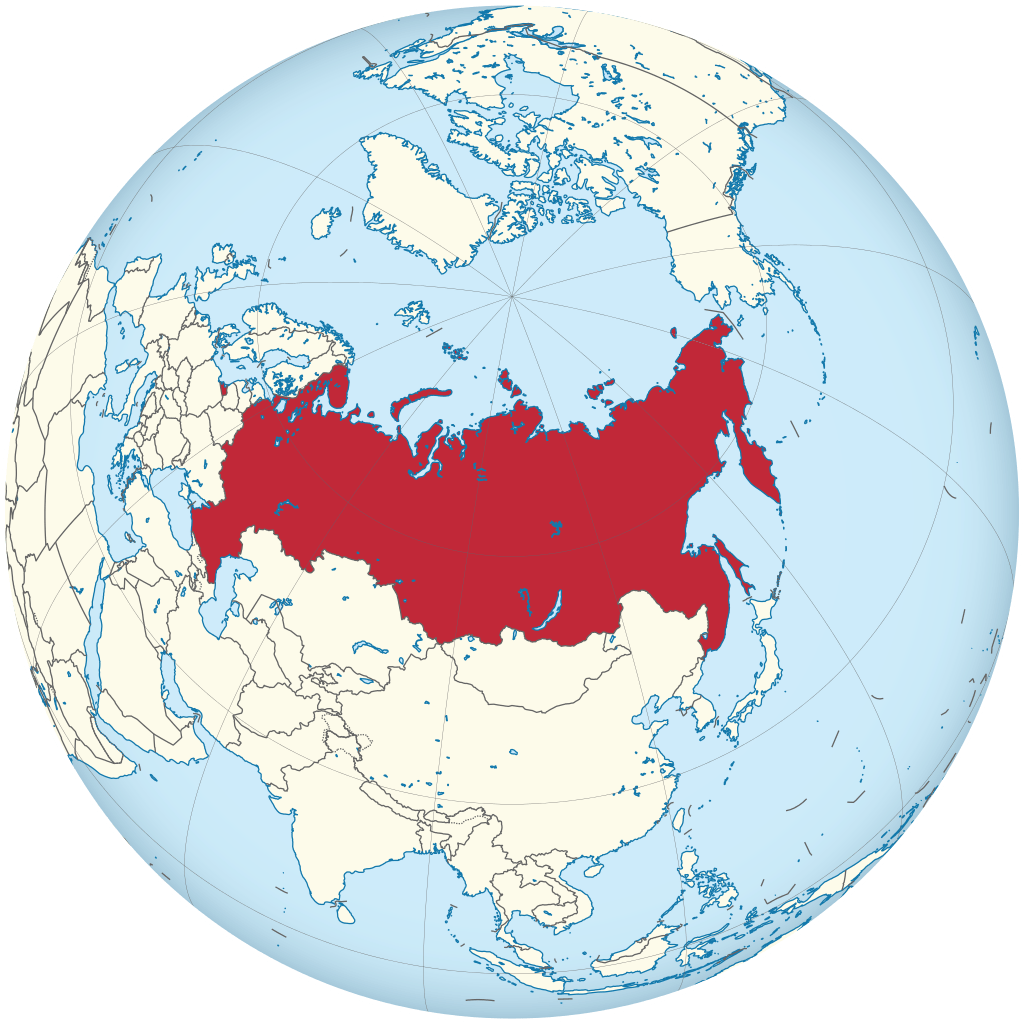

Analysts have proposed various foreign policy scenarios about the likelihood of a coming showdown between the two powers. However, most of those analyses – some of which are very good – neglect the Russian position. That country, which stretches from the Baltic to the Pacific and is ensconced between the West and China, is poised to play a pivotal role in a possible US-China confrontation due to its geography and military and economic capabilities.

Moscow believes the US-China conflict might enable it to advance the Russian geopolitical agenda, which has been much constrained by the Europeans and the Americans over the past three decades.

The current crisis between Russia and the West is the product of many fundamental geopolitical differences in both the former Soviet space and elsewhere. Relations are thus likely to remain stalled well into the future barring large concessions by one of the sides. The successful western expansion into what was always considered the “Russian backyard” halted Moscow’s projection of power and diminished its reach into the north of Eurasia – between fast-developing China, Japan, and other Asian countries and the technologically modern European landmass.

Russia claims that its western borders are now vulnerable because NATO and the EU are marching eastward. In fact, Russia has far more vulnerable territories, such as the North Caucasus and porous Central Asia.

In some respects, the Russians are simply spending too much of their national energies on problems with the West. Costly military modernization and the support for separatist regimes in Moldova, Ukraine, and Georgia weigh heavily on the Russian budget.

Russians can rightly question why their country is spending so much on the former Soviet space when Russia’s current borders are more in Asia. Why is the country investing so much in unsuccessfully disrupting Western influence in many parts of the former Soviet space? This point is doubly strong when one looks at a map of Russia, with its vast tracts of uncultivated and largely unpopulated Siberian lands.

Today, Europe is a source of technological progress, as are Japan and China. Never in Russian history has there been such opportunity to develop Siberia and transform it into a power base of the world economy.

Russia’s geographical position is unique and will remain so for another several decades, as the ice cap in the Arctic Ocean is set to diminish significantly. The Arctic Ocean will be transformed into an ocean of commercial highways, giving Russia a historic opportunity to become a sea power.

Chinese and Japanese human and technological resources in the Russian far east, and European resources in the Russian west, can transform it into a land of opportunity.

Russia’s geographical position should be kept in mind when analyzing Moscow’s position vis-à-vis the China-US competition. However, apart from the purely economic and geographical pull that the developed Asia-Pacific has on Russia’s eastern provinces, the Russian political elite sees the nascent US-China confrontation as offering a chance to enhance its weakening geopolitical position throughout the former Soviet space. Russians are right to think that both Washington and Beijing will dearly need Russian support, and this logic is driving Moscow’s noncommittal approach towards Beijing and Washington. As a matter of cold-blooded international affairs, Russia wishes to position itself such that the US and China are strongly competing with one another to win its favor.

In allying itself with China, Russia would expect to increase its influence in Central Asia, where Chinese power has grown exponentially since the break-up of the Soviet Union in 1991. Although Moscow has never voiced official concerns about this matter, that is not to deny the existence of such concerns within the Russian political elite.

However, if Moscow chooses the US side, the American concessions could be more significant than the Chinese. Ukraine and the South Caucasus would be the biggest prizes, while NATO expansion into the Russian “backyard” would be stalled. The Middle East might be another sticking point where Moscow gets fundamental concessions – for example in Syria, should that conflict continue.

Beyond grand strategic thinking, this decision will also be a civilizational choice for the Russians molded in the perennial debate about whether the country is European, Asiatic, or Eurasian (a mixture of the two). Geography inexorably pulls Russia towards the east, but culture pulls it towards the west. While decisions of this nature are usually expected to be based on geopolitical calculations, cultural affinity also plays a role.

Tied into the cultural aspect is the Russians’ fear that they (like the rest of the world) do not know how the world would look under Chinese leadership. The US might represent a threat to Russia, but it is still a “known” for the Russian political elite. A China-led Eurasia could be more challenging for the Russians considering the extent to which Russian frontiers and provinces are open to large Chinese segments of population.

The Russian approach to the nascent US-China confrontation is likely to be opportunistic. Its choice between them will be based on which side offers more to help Moscow resolve its problems across the former Soviet space.

Emil Avdaliani teaches history and international relations at Tbilisi State University and Ilia State University. He has worked for various international consulting companies and currently publishes articles focused on military and political developments across the former Soviet space.

BESA Center Perspectives Papers are published through the generosity of the Greg Rosshandler Family