BESA,By Dr. Mordechai Chaziza: China’s Maritime Silk Road Initiative

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY: The Mediterranean Sea, one of the most important maritime trade highways in the world, is the marine traffic hub at the western end of China’s Belt and Road Initiative. Beijing’s maritime strategic activities in the Mediterranean consist mainly of constructing and operating ports and railways to open up new trade links between China and the Eurasia-Africa zone. However, the implementation of a Chinese Maritime Silk Road via the Mediterranean cannot succeed unless there is a way to bridge the gap between economic interests and the capacity to protect those interests.

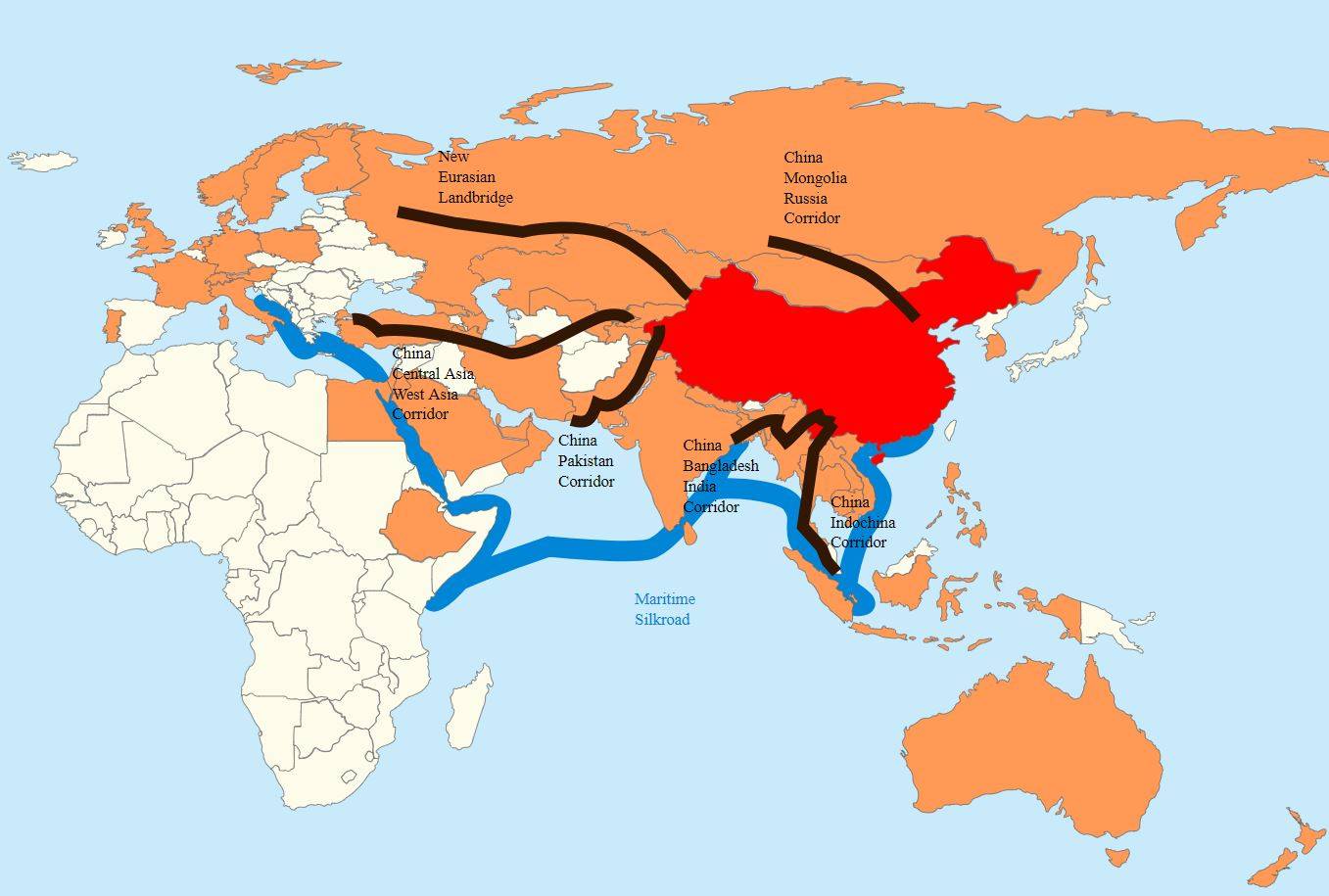

The One Belt One Road Initiative (BRI) has two components: the Silk Road Economic Belt and the 21st Century Maritime Silk Road Initiative (MSRI), which is intended to link China and Europe via land and sea routes. This initiative – Beijing’s most ambitious integration project to date – lies at the heart of China’s foreign policy. The MSRI is designed to build sea routes with faster connectivity to increase trade along the land- and sea-based Silk Road, linking Asia with Europe and Africa.

Under the strategic framework of the MSRI, China has been buying up the development and operational rights to a chain of ports stretching from the southern regions of Asia to the Middle East, Africa, Europe, and even South America. According to the Financial Times, China has spent billions expanding its port network to secure sea lanes and establish itself as a maritime power.

The Mediterranean Sea is one of the most important maritime highways of all international trade routes around the globe. It is a focal point, as it represents the western end of the BRI. Given the Mediterranean’s strategic position, China has stepped up its presence in the region by acquiring, building, modernizing, expanding, and operating the most important Mediterranean ports and terminals in Greece, Egypt, Algeria, Turkey, and Israel. Beijing wants to capitalize on the Mediterranean’s geographical proximity to become a major distribution hub for Chinese goods to the EU, its biggest trading partner.

The increasing economic ties between China and Europe are giving the Mediterranean region an opportunity to regain its place at the forefront of international trade. The newly enlarged Suez Canal, the main transport route between Asia and Europe, has doubled in terms of both capacity and traffic flow between the Red Sea and the Mediterranean. It now allows for the passage of larger vessels, reducing transit times between Asia and Europe and raising the competitiveness and visibility of Mediterranean ports.

However, access to the European market via Mediterranean ports, along with maintaining the vital flow of resources such as energy and other raw materials from the Middle East and Africa, depends on the security and political stability of the Mediterranean region. Maintaining a safe geostrategic environment and securing the geopolitical interface of the region are sine qua non conditions for the success of the construction and realization of the MSRI.

China is the world’s largest trading nation in goods. Three Chinese shipping companies are among the ten largest container-shipping companies in the world, responsible for approximately 10% of global trade. Most Chinese goods are transported by ship, so Beijing is a major destination and starting point of international shipping routes.

China’s shipping ports are among the busiest on earth. Eight of the world’s ten busiest container ports are in that country, with the port of Shanghai the busiest on the planet. China is the world’s third-largest ship-owning nation and the largest shipbuilding nation, with roughly 30 million compensated gross tones (CGT). Chinese enterprises are also active in the construction and management of ports around the world. Through the construction and management of ports and international shipping assets along the Silk Road as well as the building of faster connectivity via sea routes and an increase in trade, Beijing plans to expand China’s reach as a maritime power.

Beijing’s maritime strategic activity in the Mediterranean Sea consists mainly of constructing and operating ports or railways. These investments should be seen in the context of the country’s broader infrastructure activities under the BRI. The investment in sea lanes and railways complement each other, as they jointly open up new trade links between China and the Eurasia-Africa zone. China has slowly attempted to develop a presence in the Mediterranean by investing in international logistical distribution centers and infrastructure projects that have strengthened its regional position.

For instance, China’s investments in the Piraeus port, the ports of Ashdod and Haifa, Port Said, and the Suez Canal Corridor Project go hand-in-hand with the One Belt, One Road Initiative, which marks the passage from the Maritime Silk Road to the land-based one towards Europe. Beijing’s 21st century Maritime Silk Road should be considered a driving force for its economic and strategic interests in the Mediterranean, as well as a platform from which to accelerate and increase its regional presence and influence.

China is gradually becoming more influential economically, diplomatically, and geostrategically in the Mediterranean Sea. Huge investments and mutually beneficial trade relations between China and Mediterranean countries are increasing Beijing’s stake in regional affairs while exposing it to significant threats. The political instability and religious extremism in several countries in the wider Mediterranean region raises the question of whether Beijing would be willing to take on a leadership role, with all the responsibilities that that would entail.

There will be no successful implementation of a Chinese Maritime Silk Road without addressing the gap between economic interests and the capacity to protect those interests. Securing investments in a region of extreme geopolitical volatility will be a tough test for Beijing’s foreign policy in the coming years. China does not have an overall strategy regarding the Mediterranean region’s affairs; instead, it prefers to deal with each country bilaterally.

Chinese policy towards the region is still dominated by the economic factor, in particular trade and investment. Beijing will have to forgo strict compliance with its principle of non-interference if it wants to reap any benefits from the Mediterranean region. For the time being, China’s behavior in the region remains cautious: it is keeping a low profile and does not seek to significantly alter existing dynamics. Beijing continues to prefer to act judiciously and avoid getting involved in confrontations in the region.

Dr. Mordechai Chaziza is a senior lecturer in Politics and Governance at Ashkelon Academic College Israel, specializing in Chinese foreign and strategic relations. He can be reached at [email protected]