BRUEGEL, By Andrei Marcu and Georg Zachmann: Europe needs a fresh approach to climate strategy

The EU needs a new approach to long-term climate strategy to ensure that EU climate policy is brought in line with the goals of Paris and takes into account recent technological and political changes. Climate policy can only succeed if it does not come out of a bureaucratic ‘black box’, but is part of an inclusive process involving a wide range of stakeholders.

In Europe the debate about a new strategy to tackle climate change is beginning. The current EU climate strategy – the 2050 Low-Carbon Roadmap of 2011 – needs to be replaced. Its level of ambition (-80% by 2050) is not any more in line with the goals of the Paris Agreement, which calls for net-zero emissions by the middle of the century.

What is more, the economic, political and technological environments have changed markedly since 2011. Emission levels today are lower than expected in 2011. The failure of centralised energy and climate policy-making from Brussels has led to the emergence of a new governance framework – the Energy Union – that acknowledges the key role of member states. And while some low-carbon technologies such as batteries and solar panels have massively exceeded expectations of seven years ago, the contribution of other technologies such as carbon capture and storage (CCS) currently appear to be insufficient to the long-term goal of decarbonisation.

We believe that a sequence of climate strategies, addressing different EU needs and obligations, should be developed, and build on one another

The EU also has a formal obligation to deliver strategies for the international climate process of the UNFCCC (Paris Agreement), as well as its own internal Energy Union governance process. For these reasons the European Council of March 2018 invited “the Commission to present by the first quarter of 2019 a proposal for a Strategy for long-term EU greenhouse gas emissions reduction in accordance with the Paris Agreement, taking into account the national plans”.

Framing matters

That raises the question of what the process should be to develop this new long-term climate strategy, and what it will look like. The design of the strategy and the framing of the questions will significantly predetermine its outcomes.

Take for example the way in which emission reduction targets are defined: (1) If they are defined as an emission level to be targeted in a specific year, then an optimal strategy could be emitting large quantities of greenhouse gases until the 2040s and then switch to CCS around 2050. (2) If they are defined as a reduction target in the form of a year when net-zero emissions have to be reached, an optimal strategy could be to avoid any premature investments. (3) If the target is set as a carbon budget, i.e. a maximum cumulative amount of emissions allowed to be emitted, early action on “low-hanging fruits” such as an early coal phase-out could be optimal. Decisions need to take into account such consequences and need to be taken, if possible in cooperation with various stakeholders.

Investors might adopt a wait-and-see approach, instead of massively investing into new low-carbon alternatives, as they know that individual policies can be quickly reversed

In our new report – Developing the EU long-term climate strategy – we identify 34 choices that need to be made, for which we come up with different options. The picture becomes even more complex as many of the choices are interlinked. For instance, choosing a very long-time horizon (e.g. 2100) for the strategy might not be compatible with a quantitative modelling of the technoeconomic system.

To complicate matters further, different audiences and political processes require different, but inherently consistent, strategic guidance. Thus, the EU must: (1) develop guidance on EU climate policy and related EU member state policy; (2) deliver a strategy to the UNFCCC; (3) ensure coherence with the proposed Governance of the Energy Union regulation; (4) guide industry investment decisions; and (5) provide a vehicle for engaging EU citizens and stakeholders in decisions.

A single document meeting all these requirements will become convoluted, unfocused, and politically more difficult to approve. Therefore, we believe that a sequence of climate strategies, addressing different EU needs and obligations, should be developed, and build on one another.

Three documents

For these reasons we propose that the European Commission should publish three distinct climate strategy documents. The three documents would target political processes with different timelines and different levels of analysis and stakeholder involvement. Publishing these documents in a meaningful sequence could ensure that each plays its role in the political process.

Compared to this momentous challenge the discretionary powers of European Commission are very limited

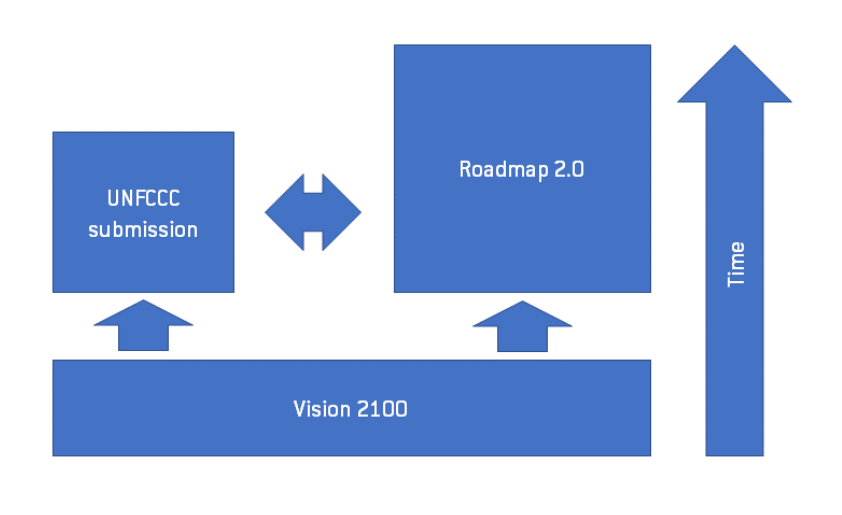

The starting point could be a relatively short document laying out a broad approach on how to decarbonise Europe in this century and thereby provide general guidance (Vision 2100 in the Figure below).

This would be followed by a comprehensive update of the 2050 Roadmap providing the analytical basis for the EU’s climate policies (Roadmap 2.0) and the EU’s submission to the UNFCCC (UNFCCC submission). As the UNFCCC submission is time-critical, that document might need to be concluded before the release of the Roadmap 2.0.

Figure 2. Potential sequencing of climate strategy documents

Wide-ranging implications

But that still does not answer the question what should be taken into account in the climate strategy and how it should be put together.

Deep decarbonisation in line with the Paris Agreement will have wide-ranging implications for the EU. By about the middle of the century, no member state will be able to use coal, oil and gas to warm houses, propel cars and generate electricity, unless this is compensated by negative emissions. Important industrial sectors will have to find ways to reduce greenhouse gas emissions that are now intimately linked to the production process.

The agricultural sector, which has largely been neglected so far, will have to play a much more prominent role in decarbonisation. And we will have to discuss how “negative emission technologies”, which are now mostly theoretical solutions, could look in reality.

Compared to this momentous challenge the discretionary powers of European Commission are very limited and the Brussels institutional setting is not geared towards unilateral top-down policy moves. As for example our experience with car emission standards or energy taxation has shown, it is unlikely that European legislation would be issued that would oblige all stakeholders to adopt the necessary changes to their economic model.

The wide-ranging nature of the decarbonisation exercise calls for a policy mix that does not confine itself to a narrow set of environmental policies

And even if such policies could be adopted, investors might adopt a wait-and-see approach, instead of massively investing into new low-carbon alternatives, as they know that individual policies can be quickly reversed if there is a temporary lack of political support.

A climate strategy is an important tool to overcome this coordination problem. It needs to define a target, show that it is feasible to get there and outline in broad terms what action is expected from each stakeholder.

But more importantly the process of developing the new climate strategy can generate the necessary broad discussion on the nature of the upcoming challenges, and how to address the inevitable trade-offs. Such a discussion is necessary to generate the long-term buy-in from stakeholders and give proper legitimacy to the climate polices which would ensure meeting the ambitious goals of the Paris Agreement. This implies that a new EU climate strategy should not be developed in a bureaucratic “black box”, but in the form of a transparent and inclusive process.

The wide-ranging nature of the decarbonisation exercise calls for a policy mix that does not confine itself to a narrow set of environmental policies but involves, among other things, trade, fiscal, macro-economic and innovation policies as well as regulatory tools in various sectors. Hence, the development of a new climate strategy should stimulate a fresh debate on how to strengthen Europe’s competitive advantage.

Editor’s note

Andrei Marcu is a Senior Fellow at the International Centre for Trade and Sustainable Development (ICTSD) in Geneva and the Director of the European Roundtable on Climate Change and Sustainable Transition (ERCST).

Georg Zachmann (@GeorgZachmann) is a Senior Fellow at the Brussels-based think tank Bruegel.

Their report – Developing the EU long-term climate strategy – appeared in April 2018.

Republishing and referencing

Bruegel considers itself a public good and takes no institutional standpoint.