James Stavridis: Here’s How to Pull Turkey Back From the Brink – Μάριος Ευρυβιάδης: Τα έωλα επιχειρήματα για την Τουρκία: Ο ανερμάτιστος Stavridis και η συμβατική σοφία των ατλαντιστών!

Erdogan gets more authoritarian, and closer to Russia and Iran, every day. But kicking him out of NATO would make things worse.

Since its founding nearly a century ago, Turkey’s foreign policy goal has been summed up in a simple phrase: “No problems with our neighbors.” But the situation today is different: “all our neighbors have problems.” And the Turks have plenty of their own.

There is no understating how important it is that the U.S. and other NATO allies quickly mend fences with Turkey and help it through its regional crisis.

The Turks are under great strain from the fight against terrorists in Syria and Iraq, a rare instance of sustained warfare along NATO’s southern flank. Russia is moving ever closer to Turkey, coordinating military operations in the Middle East and agreeing to sell the Turks a top-of-the-line S-400 air-defense system, over protests from the U.S. and other NATO countries.

Domestically, President Recep Tayyip Erdogan is a highly polarizing figure who continues to fume over the failed coup against him last summer. More than 50,000 Turks have been jailed and 150,000 have lost their jobs, actions that will reverberate in Turkish politics for a generation. Crackdowns against “unruly journalists” and “suspect jurists” are common. And the independence movement among the Kurds of Iraq and Syria has put an end to hopes for progress on relations with Turkey’s own restive Kurdish minority.

Meanhwile, U.S.-Turkish relations have cratered following a string of confrontations that run from the profound to the petty. Erdogan continues to be obsessed with extraditing Fethullah Gulen, a Turkish cleric now living in Pennsylvania, whom he believes to have been at the heart of the coup. His security detail is under indictment in the U.S. after they beat a group of protesters in Washington. This month, a Turkish citizen working for the U.S. State Department was jailed, triggering visa retaliations back and forth between Ankara and Washington and dealing a staggering blow to the Turkish lira. And the U.S. is understandably concerned about Turkish moves in Syria, which seem to be more aligned with the interests of Russia and Iran than the U.S.

This has led some U.S. critics to wonder whether NATO might be better off without Turkey as a member. That is a foolish thought. Rather, as we confront the lowest point in U.S.-Turkish relations in a generation, we need to think through a meaningful strategy for bringing this crucial partner back into the fold. What should the U.S. and its NATO allies do?

First, we need simply to accept Turkey’s fundamental strategic importance. When I was the supreme allied commander of NATO forces, people would often say to me, “Turkey is a crucial bridge between East and West.” Actually, Turkey is much more than just a bridge. Such comments miss the power, importance and history of Turkey, which is in every sense a power center unto itself. Over the centuries of the Ottoman Empire, the Turks proved their ability to build a powerful economy, conduct complex imperial politics, and dominate vast swaths of territory throughout Europe, the Middle East and Africa.

Today, Turkey has the 13th-largest economy in the world, a growing population of 80 million, a powerful diaspora around the world (including within Europe and the U.S.), and a highly diversified economic base. It also has the second-largest army in NATO and hosts the headquarters of all alliance land forces. The military is highly professional (albeit battered at the senior-leadership level in the face of post-coup purges). Turkey is a powerful and important actor throughout the Middle East now, and will be a significant global player by mid-century. None of this can be ignored.

Second, we must articulate and execute a strategic plan for engaging the Turkish government. Any rapprochement with Ankara must include conducting more frequent political visits at every level, especially cabinet and immediate sub-cabinet U.S. officials visiting their counterparts. Western governments should encourage more direct business investment and a higher level of technology transfer in sectors such as light industry, cyber and robotics. The U.S. must involve Turkish leaders and concerns as it tries to resolve the crises raised by the independence movement in Iraqi Kurdistan. The U.S and Europeans should also help conduct humanitarian operations including joint efforts in the massive refugee camps along the Turkish-Syrian border, which are costing Erdogan’s government a fortune.

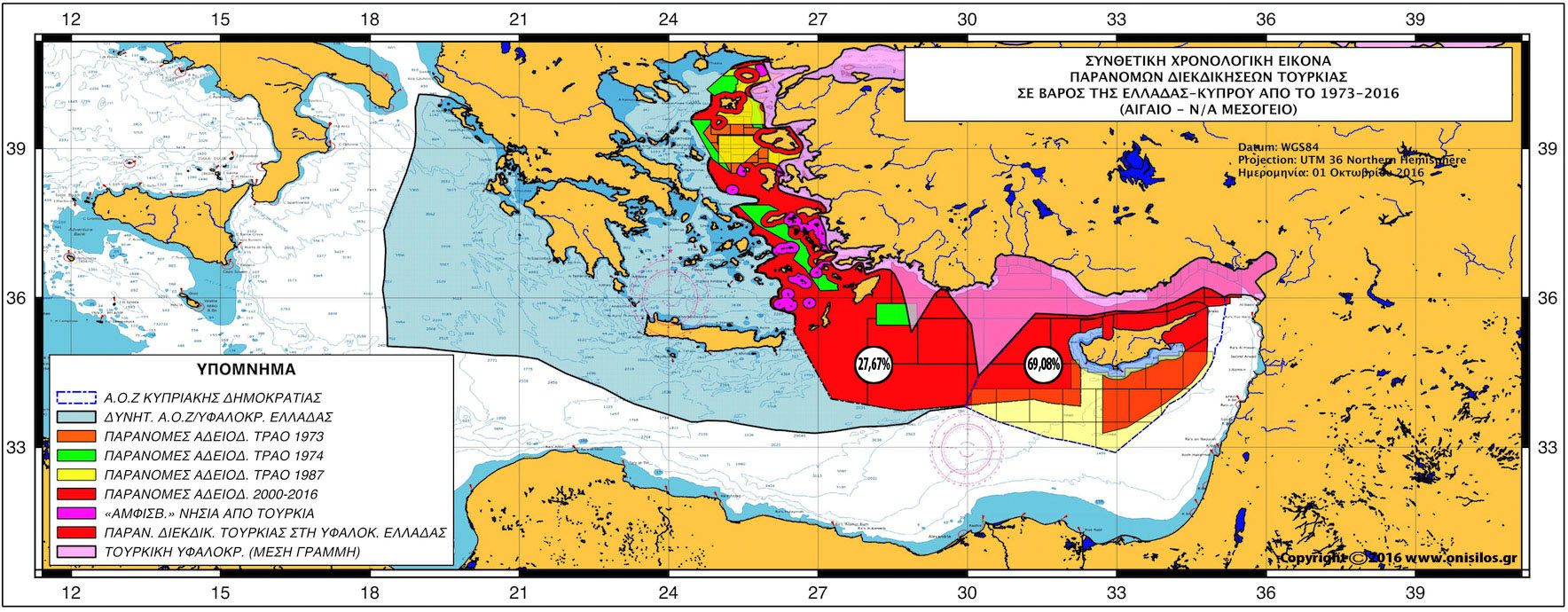

Third, the U.S. can encourage geopolitical relationships that keep Turkey oriented toward the trans-Atlantic world. These would include helping to ease tensions with Greece over the Aegean and the flow of refugees; resolving the long-standing dispute over Cyprus (which is closer to a possible solution than it has been in decades); helping to rebuild a once-strong relationship with Israel that has frayed among arguments over everything from the Kurds to the status of Jerusalem; and helping melt tensions with the Sunni Arabs, who feel threatened by the Turkish moves to align with Iran. Above all, the U.S. should encourage the Europeans to at least continue negotiations on possible EU membership for Turkey, which unfortunately has never looked so distant).

Fourth, we must find a modus vivendi with President Erdogan. He is clearly in control of his country’s destiny, and will remain in power for the foreseeable future. Yet his increasingly dictatorial tendencies will create real tension with Washington. We should adopt a strategy of criticizing in private while working visibly with him in public. Creating public confrontations will not help — we need deft personal diplomacy to encourage him to ensure the long term viability of democracy, rule of law, and freedom of the press.

Finally, we can enhance military-to-military cooperation. This means more exercises and training missions in Turkey, both with the U.S. bilaterally and through NATO; better information and intelligence sharing, especially in regard to operations in Syria; more U.S. military sales to Ankara (particularly now that Russia has established itself as a competitor); naval exercises in the Black Sea with Turkey alongside other NATO Allies and partners (Romania, Bulgaria, Georgia, Ukraine); joint missions for humanitarian and security operations in Kosovo and Bosnia; and high-level military delegations exchanging visits.

None of this will be easy or cost-free. But it would be a geopolitical mistake of enormous proportions to allow Turkey to drift away from the U.S., Europe and NATO. We are in danger of seeing that shift occur before our eyes, and we need a plan to prevent it. That will mean rising above some of the heated rhetoric in the relationship to keep our eyes on the strategic value of Turkey as a friend, partner and ally.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Πηγ’η: https://www.bloomberg.com/view/articles/2017-10-20/here-s-how-to-pull-turkey-back-from-the-brink

Μάριος Ευρυβιάδης: Τα έωλα επιχειρήματα για την Τουρκία: Ο ανερμάτιστος Stavridis και η συμβατική σοφία των ατλαντιστών

Για πρώτη φορά μετά την τουρκική εισβολή του 1974 η «ατλαντική Τουρκία» του ΝΑΤΟ, ο «μεγάλος και πιστός σύμμαχος» των ΗΠΑ και του Ισραήλ, υποφέρει από αρνητική δημοσιότητα στην Αμερική. Και επιστρατεύονται όλοι οι πολιτικά και οικονομικά εξωνημένοι για να υπερθεματίσουν υπέρ της Τουρκίας και πως αυτή διατηρεί ακόμη ανέπαφη, 20 σχεδόν χρόνια μετά το τέλος του Ψυχρού Πολέμου, τη στρατηγική της αξία για τις ΗΠΑ και την ατλαντική Ευρώπη του ΝΑΤΟ.

Το πιο πρόσφατο παράδειγμα της σχολής αυτής είναι η αρθρογραφία του πρώην διοικητή του ΝΑΤΟ και των αμερικανικών δυνάμεων στην Ευρώπη και σημερινού Κοσμήτορα στη Σχολή Νομικής και Διπλωματίας (Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy, Tufts University) James Stavridis και η οποία δημοσιεύθηκε στη γνωστή αμερικανική επιθεώρηση Bloomberg (20/10/17).

Τα επιχειρήματα του Stavridis συνοψίζουν τη διαχρονική συμβατική σοφία των ατλαντιστών ως προς τον κομβικό ρόλο της Τουρκίας στους στρατηγικούς σχεδιασμούς της Δύσης για την αντιμετώπιση της Σοβιετικής Ένωσης και Ρωσίας σήμερα, τον ρόλο της ως «ανάχωμα» αλλά και ως «μοντέλο» κατά εξτρεμιστικών ιδεολογιών (σήμερα, δηλ. του ισλαμιστικού φονταμενταλισμού αλλά που λόγω σκοπιμοτήτων δεν ονομάζεται έτσι), για την «αμυνα» του Ισραήλ καθώς επίσης και για τον «έλεγχο» του Ιράν.

Θα παρουσιάσω συνοπτικά τα πέντε επιχειρήματα του Stavridis και θα προσπαθήσω να απαντήσω κατά πόσον συνεχίζουν αυτά να ισχύουν σήμερα αλλά και γιατί αυτά αναπαράγονται συνεχώς εδώ και σχεδόν επτά δεκαετίες.

Το πρώτο και πιο βασικό επιχείρημα, και από το οποίο συνάγονται τα υπόλοιπα, είναι πως η Τουρκία διατηρεί «στρατηγική αξία» που πρέπει να «γίνει αποδεκτή» και πως είναι αυτόνομος «χώρος ισχύος».

Το δεύτερο, πως οι ΗΠΑ οφείλουν να «δημιουργήσουν και να υλοποιήσουν ένα στρατηγικό σχέδιο» επαφής με την Τουρκία.

Το τρίτο, πως οι ΗΠΑ θα πρέπει να ενθαρρύνει τέτοιες «γεωπολιτικές σχέσεις που να διατηρούν την Τουρκία προσανατολισμένη προς τον ατλαντικό κόσμο».

Τέταρτο, πως πρέπει να βρεθεί από τις ΗΠΑ ένας τρόπος (modus vivendi) με τον Ερντογάν και να αποφεύγονται οι δημόσιες αντιπαραθέσεις μαζί του.

Και πέμπτο, πως οι ΗΠΑ πρέπει να καλλιεργήσουν τη «συνεργασία ανάμεσα στις στρατιωτικές ηγεσίες των δυο κρατών», να εντατικοποιήσουν τις σχέσεις της Άγκυρας με το ΝΑΤΟ, να αυξήσουν τις πωλήσεις όπλων, να κάνουν κοινά γυμνάσια στη Μαύρη θάλασσα, κλπ.

Καταρχήν σημειώνω πως κατά τη «λογική» Stavridis, τα πράγματα είναι μονόδρομος: η Τουρκία είναι τόσο «σημαντική» για τις ΗΠΑ ώστε το βάρος διατήρησης της σχέσης να εναπόκειται στη Ουάσιγκτον και μόνο. Το ζήτημα της αμοιβαιότητας αγνοείται επιδεικτικά.

Η θέση αυτή χαρακτήριζε και δικαιολογούσε όλη την πολιτικό-στρατηγική σκέψη στις ΗΠΑ και κυρίως στο Πεντάγωνο έναντι στην Τουρκία στη διάρκεια του Ψυχρού Πολέμου, αλλά προφανώς και τώρα. Εάν δηλαδή η Τουρκία «χαθεί» σήμερα για τις ΗΠΑ, όπως π.χ. «χάθηκε» η εθνικιστική Κίνα το 1949 ή το Ιράν το 1978, το φταίξιμο δεν θα είναι των Τούρκων, (σήμερα δηλ. του ισλαμιστή Ερντογάν) αλλά των Αμερικανών. Ταυτόχρονα, η θεώρηση αυτή «παρήγαγε», από το 1947 και μετά, την αντίστοιχη θέση της Τουρκίας και, μάλιστα σε τέτοιο βαθμό, που ο μακαρίτης Τούρκος πρωθυπουργός Σουλεΐμάν Ντεμιρέλ να λέει σε πρώην Αμερικανό αξιωματούχο το 1979, «πρέπει να πληρώνετε τους λογαριασμούς μας διότι μας έχετε ανάγκη» («you must pay our bills because you need us»).

Έχουν όντως έτσι τα πράγματα όπως πριν 70 σχεδόν χρόνια όταν άρχισε ο Ψυχρός Πόλεμος; Αδιαμφισβήτητα η Τουρκία είναι στρατηγικής σημασίας χώρα. Όμως το στρατηγικό βάρος μια χώρας και συνεπώς η ισχύ και επιρροή της στα διεθνή δρώμενα είναι πάντοτε σχετική με τα πράγματα και την ισχύ και τον ρόλο άλλων κρατών, είτε αυτά είναι ανταγωνιστές είτε είναι συνεργάτες.

Μετά το τέλος του Ψυχρού Πολέμου η Τουρκία «έχασε» τη στρατηγική της αξία ως «αμυντικός/επιθετικός» χώρος έναντι της Σοβιετικής Ένωσης και του κομμουνισμού. Ας μην ξεχνάμε πως μετά το 1991 η Τουρκία έπαψε να έχει σύνορα με τη σημερινή Ρωσία (ήταν 800 χιλ. επί Σοβιετίας!). Και σήμερα η Τουρκία κάθε άλλο παρά εχθρός είναι της Ρωσίας και του Πούτιν.

Αυτό που αρνείται να «καταλάβει» ο ατλαντιστής Stavridis και οι ομόσταυλοί του, είναι πως τα πράγματα δεν έχουν πια έτσι. Ο κόσμος άλλαξε και σίγουρα άλλαξε και η Τουρκία. Η αλλαγή της Τουρκίας έναντι της Δύσης δεν άρχισε επί Ερντογάν αλλά ούτε και «εμπνεύστηκε» από αυτόν. Η αλλαγή έχει βαθιές κεμαλικές καταβολές αλλά αυτό είναι μεγάλο κεφάλαιο για να αναλυθεί εδώ. Επί Ερντογάν, όμως, τα πράγματα έχουν «ξεχειλώσει» και το «μάζεμα» τους δεν μπορεί να γίνει με έωλες στρατηγικές και ψυχροπολεμικές νοοτροπίες.

Δομικό και βαθιά πολιτικό το πρόβλημα

Τι δεν καταλαμβαίνει ο James Stavridis; Δεν καταλαβαίνει πως η Τουρκία «Πακιστανοποιείται» πολιτικά και θρησκευτικά και πως ο αμετροεπής Ερντογάν δεν είναι παρά ένα σύμπτωμα του όλου προβλήματος.

Το ουσιαστικό πρόβλημα της Τουρκίας είναι δομικό και παράλληλα βαθιά πολιτικό. Όπως εύστοχα παρατήρησε ένας Τούρκος διανοούμενους τη δεκαετία του 1950 ονόματι Celal Yaliniz- όταν τότε οι ατλαντιστές την εξυμνούσαν ως κοσμικό, φιλελεύθερο, αναπτυξιακό και αντικομουνιστικό «μοντέλο»- η Τουρκία είναι ένα πλοίο που ταξιδεύει ανατολικά και οι επιβάτες του στο κατάστρωμα βαδίζουν δυτικά. Σήμερα με τον Ερντογάν στο πηδάλιο ο προσανατολισμός των Τούρκων έχει ευθυγραμμιστεί με την πορεία του πλοίου. Του Stavridis όμως o προσανατολισμός παραμένει ανερμάτιστος. Όπως και της συνομοταξίας του στην Ουάσιγκτον.

ΠΗΓΗ:https://www.apopseis.com/ta-eola-epichirimata-gia-tin-tourkia-o-anermatistos-stavridis-ke-i-symvatiki-sofia-ton-atlantiston/